TO WARIS SHAH BY AMRITA PRITAM - A COMPREHENSIVE ANALYSIS

CONTENTS:

1. Introduction to Amrita Pritam and The Poem

2. About Waris Shah

3. About Heer Ranjha

4. Partition - a Historical Background

5. Summary of The Poem

6. Main Theme of The Poem

7. Imagery Used in The Poem

8. References

Introduction to Amrita Pritam And The Poem:

Amrita Pritam (1919-2005) was born in Gujranwala. She began writing at an early age, and her first two collections of verse, Thandian Kiranam (The cold Rays) 1935 and Amrit Lehran (The Ambrosial Waves) 1936, are sentimental homilies that use conventional motifs and themes. It is only after she came under the influence of Marxian thought and idiom of the Progressive Writer’s Movement that she began writing social and political poetry. One of her important works of this period is Pattar Gite (Gravel Stones) 1940, at the time of the partition she moved to New Delhi, where she began to write in Hindi as opposed to Punjabi, her mother tongue.

This poem “To

Waris Shah” (1949) originally called ‘Ajj Akhan Sah Nun’ and included in her

volume of Punjabi verse called Main Twarikh Han Hind Di (I am the historian of

Hind) is a hauntingly beautiful poem addressed to the author of the immortal

epic of love, Heer Ranjha. It is a plea for a return to the days of love and

brotherhood among the people of Punjab. Heer Ranjha is a love story and is an

allegory of the living culture of eighteenth-century Punjab, where the poet

recalls with nostalgia and longing. The partition of India in 1947 had a great

impact on Indian literature, especially writings of Hindi, Urdu and Punjabi.

The transfer of populations and the never-ending communal riots challenged the

writers of the time to take up their pens and stem the tide of hatred and

bloodshed by advocating humanity, peace and brotherhood.

“To Waris Shah” is

an expression of the poet’s horror and sense of shame and indignity at the brutal

ways of men. In this poem she expresses her agony at the condition of the

bleeding and ravaged land. The historical analogue that is invoked from the

outset, adds to the sense of poignancy and pain. Amrita Pritam’s appeal is to

both poetry and history and she summons to her aid the greatest medieval love

poet of Punjab.

About Waris Shah:

Hailed as the Shakespeare of undivided Punjab,

Waris Shah, born on January 23, 1722, Jandiala Sherkhan, Pakistan, was a

Punjabi Sufi poet of the Chishti order known for his unparalleled contribution

to Punjabi literature in the penning of the timeless love legend ‘Heer. Heer

is considered one of the quintessential works of classical Punjabi literature.

The story of Heer was also told by several other writers—including notable

versions by Damodar Das, Mukbal, and Ahmed Gujjar—but Waris Shah's version is

by far the most popular today. Born into a reputed Syed family who claimed

descent from Prophet Muhammad, Waris Shah claimed himself as a disciple of Pir

Makhdum of Kasur. Waris Shah's parents are said to have died when he was young,

and he probably received his education at the shrine of his preceptor. After

completing his education in Kasur, he moved to Malka Hans, a village twelve

kilometers north of Pakpattan. Here he resided in a small room, adjacent to a

historic masjid, now called Masjid Waris Shah. His mausoleum is a place of

pilgrimage today, especially for those in love. As he is also known as the

Shakespeare of the Punjabi language, some critic say that through this story of

romantic love, he also intended to portray the love of Man for God. He was a

consummate artiste, deeply learned in Sufi and domestic cultural lore. His

verse is a treasure-trove of Punjabi phrases, idioms and sayings. His minute

and realistic depiction of each detail of Punjabi life and the political

situation in the 18th century, remains unique. Waris Shah also

sublimated his own unrequited love for a girl (Bhag Bhari) in writing romance.

Though he has not been included in the list of Saint poets like Khawaja

Maood-ud-Din Ganj Shakar and Ali Hajveri, his richness in poetry that touched

the heart and soul of a common Punjabi makes him a unique writer. Many verses

of Waris Shah are widely used in Punjabi till date and is so popular even after

250 years. 1964 Pakistani film titled “Waris Shah” and 2006 Punjabi film “Waris

Shah: Ishq Daa Waaris.” Waris Shah Poetry allows

readers to express their inner feelings with the help of beautiful poetry.

Waris Shah shayari and ghazals is popular among people who love to read good

poems. Some of his well know poems are as follows:

Asli Heer Waris Shah.

Hazrat

Waris Shah. Monograph. 2012.

Heer

Waris Shah. Ma Urdu tarjuma. 2006.

Heer

Waris Shah. Manzoom Urdu Tarjuma. 1976.

Maqamat-e-Waris

Shah. Mutala-e-Heer Ki Raushni Mein. 1999.

Qissa

Heer. Volume-002.

Shajra-e-Tayyibah

Qadriyyah Warsiyah. 1892.

About Heer Ranjha:

Heer

Ranjha, also known as Heer

and Ranjha, is one of the tragic

love stories of Punjab. There are various versions of Heer Ranjha, the version

of Waris Shah was popular among all, written in 1766. This is a story of denied

love between Heer and Ranjha.

After getting to know about the love that they had for each other, Heer’s family accepted to marry each other. Heer and Ranjha were happily getting ready to get together, but that happiness was short-lived. Heer’s uncle, who doesn’t want them to get together provides food to Heer which was mixed with poison so that their marriage wouldn’t happen. Unaware of that, Heer consumed her food and died. When Ranjha saw Heer dead, he too, ate the poisoned food and died along with her

Amrita Pritam, uses the reference to the story of Heer Ranjha by Waris Shah, to indicate that, like Heer, there are many women in Punjab who are suffering and are murdered due to the partition of India-Pakistan in 1947. Amrita wanted Waris Shah to stand with these women, as he did to Heer, and write about how women suffer due to the barbaric nature of men.

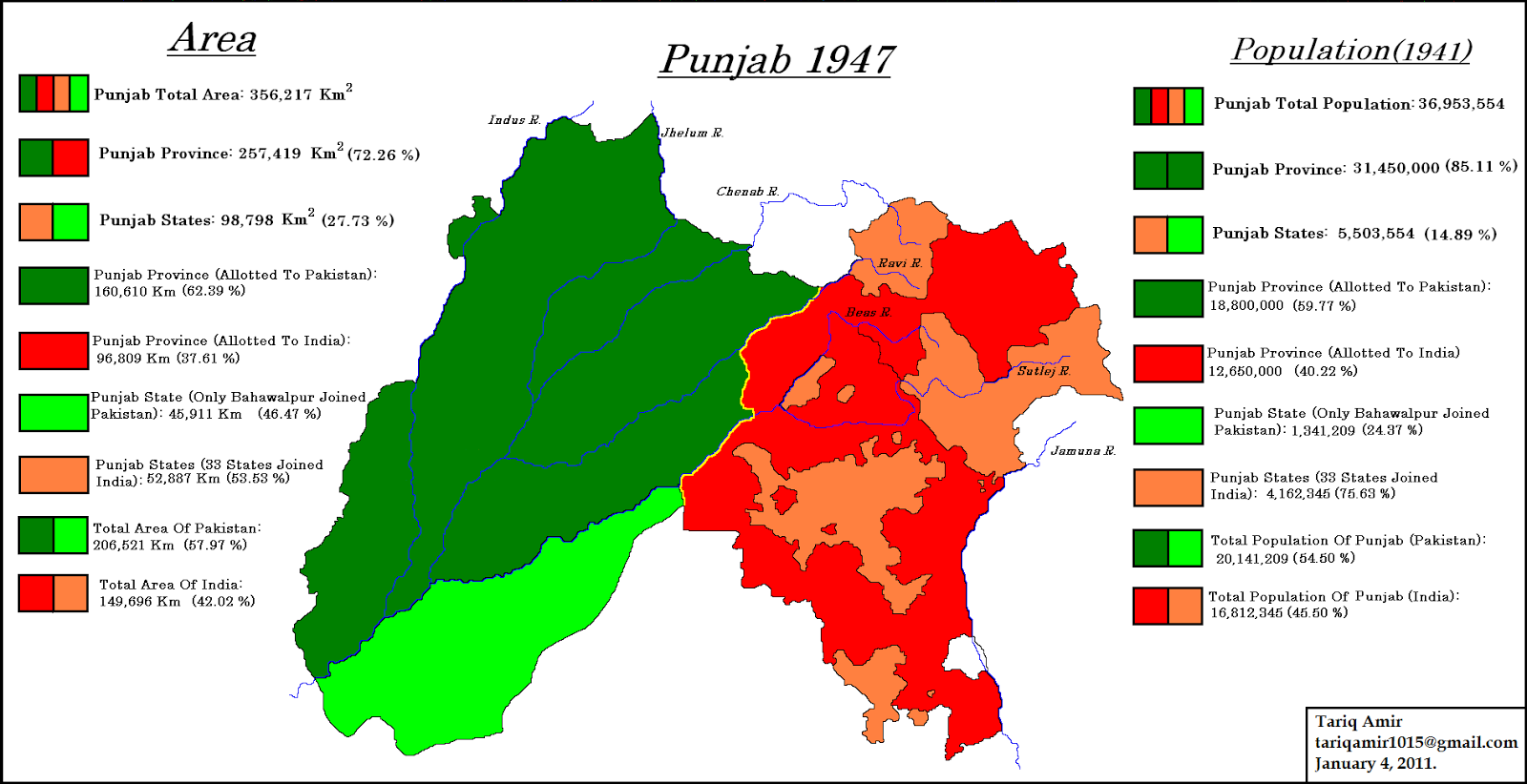

Partition - a historical background:

The partition of India was the process of

dividing the subcontinent along sectarian lines, which took place in 1947, when

India got freedom from British. The plan was written by Cyril Radcliffe,

who wrote it based on a British commissioned report on India. The plan was

finalized on July 18, 1947 and was put into action a month later. The partition

divided the country into the countries of India and Pakistan. One reason for

partition was the 2 rule nation theory by Syed Ahmed Khan stated that Muslims

and Hindus were too different to be in one country.

The impact and aftermath of the partition devasted the country. Riots

erupted and looting broke out widespread. Women were raped and battered by both

the Hindus and Muslims and trains full of battered women and children would

arrive between the borders of India and Pakistan daily. Over 15 million

refugees were forced into regions completely new to them. Even though they

shared the same religion their family and ancestors grew up in. The provinces

of Bengal and Punjab were divided causing outrage in many Muslims, Hindus and

Sikhs alike. Even after almost six decades, after the partition, India and

Pakistan have been to war twice since the partition and Pakistan suffered the

bloody war of the breaking away of East Pakistan and Bangladesh. The two

countries are still arguing over the land locked region of Kashmir. Many

believe the partition not only broke the unity of India, but also took away the

sense of belonging to many people who

were tore apart from their native regions.

In

the poem, Unto Waris Shah, Amrita Pritam depicts the effects of partition of

Punjab and portrays the bloody chapters of the territorial division of India. She feels that partition

of India snatched everything away from the innocent people of Punjab. It

snapped the invisible thread of love and existing among people.

Summary of the poem:

Amrita Pritam is

witnessing the bloodbath happening all around her motherland. The condition of

Punjab is hurting her deeply. At this critical moment, she resorts to the poet

of love and compassion, Waris Shah. He is no more. The people of Punjab have

forgotten his words of pure love. They are now fighting and killing their own

countrymen ruthlessly. She wants to spread the message of Heer and Ranjha at

this chaotic moment.

The poetess needs the

assistance of Waris Shah badly. She is requesting him to appear again as the

moment needs him the most. The people of Punjab have killed enough people that

it turned the water of Chenab crimson red. The act of partition has impregnated

evil spirit into the hearts of people. Now the green pastures of Punjab have

turned into a graveyard. Corpses are lying here and there. Such was the

condition of Punjab at the time of partition.

Amrita Pritam thinks that some satanic force is responsible for all this hurly-burly. It has contaminated the tributaries of the river Indus with poison. The water is now irrigating the land with poison. It is the poison of “Divide and Rule Policy” which is irrigating the spirit of an Indian. This poison like the diabolic policy is the root cause of what is happening around the poetess.

The fertile land of

Punjab is now giving birth to poisonous saplings. Amrita Pritam compares the saplings to hatred of

men metaphorically. The hallucination of “otherness” is ultimately a threat to

the integrity and unity of India.

The poison of revenge

has intoxicated the commoners. The beautiful natural landscape of Punjab is now

turned into a field of mass-slaughter. That’s why Amrita Pritam writes,

“Scarlet-red has turned the horizon/ and sky high has flown the curse./ The

poisonous wind,/ that passes through/ every forest,/ has changed the/

bamboo-shoots into cobras.”

This metaphorical

cobra is biting the people of Punjab and inserting its venom into their bodies.

The poetess is pointing here to the selfish political leaders who are trying to

destroy love, compassion, and brotherhood from people’s hearts by spreading its

venom. Amidst all of this, the daughters of Punjab are the most affected. They

have stopped singing. The “spinning wheel”, metaphor of “rural economy”, has

stopped its functioning. Girls are running to save their lives. They can’t

attend the trinjan to sing together, to share their sorrows, and to help each

other in this critical situation. Even the couples who have married recently to

live a happy life, are fleeting to save their lives.

Partition of India snatched everything away from the innocent people of Punjab. It snapped the invisible thread of love existing among people.

The men of Punjab

aren’t in the mood of blowing the flute. They are indulged in fighting and

killing each other. Blood is spread everywhere. According to the poetess, even

the dead will start weeping after seeing this horrid picture of Punjab.

In utter anguish, the

poetess says that the men of Punjab have turned into villains. They have become

the “thieves of love and beauty” for the poet. After seeing all this the writer

can’t hold her tears. She desperately needs the help of Waris Shah whose words,

she thinks, can stop this turbulence. The refrain used at the end of the poem,

emphasizes her sincere prayer to the dead poet.

Main theme of the poem:

The main

theme of this poem is violence and bloodshed. In the context of the time period

and the poet’s homeland being Punjab, we can understand that the violence is

caused by the event of Partition.

The poem is

addressed to Amrita Pritam’s muse, classic Punjabi poet, Waris shah. Through

the poem, Pritam expresses the extreme anguish and helplessness that she feels

witnessing the destruction of her people and her homeland due to manmade

communal and religious differences and conflicts.

The theme

of violence is expressed through vivid and gory descriptions of literal, actual

events that has historically happened in Punjab during the partition period,

like the deaths of a large number of people with their corpses strewn over her

land everywhere, the rural economy of handloom going through loss and downfall

due to the extreme communal riots happening throughout Punjab, and the violence

making the survival primary so art and creativity has come to a screeching

halt.

All these

real incidents are also metaphorically expressed by interesting imagery. The rivers

of Punjab being metaphorically poisoned by the bloodshed, which in turn poisons

the crops and land through irrigation, which in turn poisons the hearts of the

people themselves, instigating them to continue the cycle of violence. Another

metaphor is used when the bamboo trees are turned into serpents intoxicating

the commoners with it’s toxic venom that doesn’t have any antidote. Pritam uses

this antidote less venom and poison to mankind’s inherent penchant for violence.

Pritam ends

the poem by helplessly hoping that only by waris shah, the poet who amplified

the voice of a voiceless woman, waking up from the dead, and using his art to

once again magnify the violence that is currently happening in her homeland,

could possibly bring a stop to the vicious cycle of bloodshed that is taking

place due to the partition.

Imagery used in the poem:

“To

Waris Shah” powerfully conjures a sense of place by drawing on images of the

Punjabi landscape and rural life: the fields, the river Chenab, the earth, the

spinning wheels and the peepal tree. Waris Shah’s Heer begins in a similar way,

with detailed descriptions of Takht Hazara, the village where Ranjha lived with

his brothers and father. Hazara is described as “paradise on earth,” a

bountiful hamlet whose inhabitants, ostensibly seem to engage in little more

than merriment. His hyperbolic description of Takht Hazara with a stanza

exposing the corrosive jealousy of Ranjha’s brothers towards him. The brothers

are compared to venomous snakes that strike Ranjha’s heart mercilessly,

completing the biblical imagery by placing a serpent in paradise. Pritam similarly

evokes the geography of the land, complementing her description of the

landscape with tropes from the folk tradition such as Ranjha’s flute and the

girls’ trinjann. The juxtaposition of the physical landscape with regional

cultural symbols conjures a counter cartography of Punjab—constituted neither

by the imperatives of the colonial state, nor by the aspirations of the

mainstream nationalist movement. Her verse constructs a cultural geography of

the region, its contours sketched by the qissa of Heer. Yet Pritam’s grounding

in a pre colonial literary tradition does not lead to a romanticized view of

region and community as the primordial, utopic martyrs of colonial oppression

and nationalist modernity. As the poem progresses, Pritam’s deployment of the

Heer narrative deepens her analysis of the nexus between Punjabi patriarchy and

Indian/Pakistani nationalism. Just as in Waris Shah’s Heer, the serpent and its

poison become central to establishing this linkage. Heer Waris Shah makes

repeated use of the serpent motif that reappears in the description of Kaido,

Heer’s uncle and nefarious village outcast, who exposes the lovers to the

village council and plays an instrumental role in marrying Heer off forcefully.

The serpent, used exclusively to refer to male characters, appears first in

Takht Hazara to signify the corruption wrought in familial relations by greed,

and then to represent the need to regulate women’s bodies and sexuality. It

becomes a symbol of patriarchal control and toxic masculinity, lurking

menacingly in the domestic and the public sphere, in Ranjha’s home and in

Heer’s village. However, in the aftermath of Heer’s altercation with the Qazi,

once she is married and forced into a palanquin, the serpent and poison motif

undergoes a subtle transformation.The wretched and poor become both sufferers

and perpetrators—as the pomp and splendor of Heer’s dowry comes to represent

economic exploitation, a regime under which “they are robbed in their own

homes.”Pritam reworks this play on “dissolving poison” to analyze the carnage

and social devastation wreaked during Partition. In her poem, this idea of

venom or poison is generalized into ideology, which in this case, takes the

form of a masculine nationalism informed by communal consciousness. Thus, “To

Waris Shah'' underlines the destructive and inter-related role of colonial

complicity, nationalist ideology, regional patriarchy and religious identity in

creating a situation in which ordinary people turned to killing their own

neighbors, “their grief directed towards one another” . She develops the

serpent metaphor to give us the powerful image of venom being dissolved into

the land itself, spreading through the life-giving flow of the river that

subsequently “drenched the earth” itself:Similar to the “stirred poison” in

Waris Shah’s verses, the venom is no longer an external agent acting on the

body of Heer, who is eventually, significantly, poisoned in the story—it is

toxic matter that has seeped into the very substance of the body politic of

Punjab. Pritam also hints at colonial complicity in nurturing this beast

through policies that communalized identity in Punjab, suggested by the

othering tone of “somebody dissolved poison into the rivers”.

The usage of colours in a literary work of art elevates its tone and mood. Likewise, Pritam here represents a kaleidoscopic vision of Punjab and the wrath of partition. The hues of blue,red,pasture green, spritiless graves. The colour blue symbolizes the need of freedom juxtaposed to death in the poem. Red is the representation of agony, pain and bloodshed caused due to the heinous law of the Divide and Rule Policy, while the viridescent lands are irrigated with venom that would uproot the land of five rivers forever.

In many ways, Pritam exaggerates and extends Waris’s symbolism to mark the enormity of historical rupture created by Partition in Punjab, as the bamboo flute, the pristine symbol of Ranjha, also undergoes this heinous transformation. As Punjab is carved up, the venomous serpent of patriarchal ideology grows into a ferocious Hydra, it’s many-headed form signifying the convergence of the “multiple patriarchies [national, colonial and communal] at work in women’s lives.She establishes her feminist revisionist intent from the very outset, as the poem’s opening invocation of Waris Shah can easily be read in the tone of a sharp rebuke—speak Waris Shah, you are dead and long gone, but arise from your grave, for you must! The sheer scale of violence in the Partition, abductions and murders of women calls for this macabre resurrection of the poet who penned the most beloved ballad of the land. Yet this resurrection is not merely an act of nostalgia stemming from a romantic sense of cultural loss—it is also Pritam’s attempt to prize away male authorial privilege to fashion a feminist reworking of cultural identity and nationalist critique that becomes imperative to the nascent process of nation-building. Much like Heer’s hermeneutical challenge to the Qazi at the height of crisis in the narrative, a woman must rise to the task of re-interpreting tradition and appropriating the intellectual tools of the male at a time of great upheaval following decolonization.

References:

- Pritam. 1979. “To Waris Shah.” Pp. 11 in Alone in the multitude, edited and translated by S. Kohli. New Delhi: Indian Literary Review.

- Shah, Waris. 2006. Hir Waris Shah. Lahore: Millat Publications.

- https://scroll.in/article/847004/when-amrita-pritam-called-out-to-waris-shah-in-a-heartrending-ode-while-fleeing-the-partition-riots

www.sufinama.org

www.poemhunter.com

www.pinjabi-kavita.com

www.hindustantimes.com

www.allpoetry.com

https://www.gcsnc.com/cms/lib/NC01910393/Centricity/Domain/5457/The%20Partition%20of%20India%20PowerPoint.ppt

https://poemanalysis.com/amrita-pritam/i-say-unto-waris-shah/

Indian Literature: An Introduction - University Of Delhi

Blog Done By:

Anulekha M - 2113312005005

Gayathri S - 2113312005012

Meenakshi S - 2113312005025

Sahana Pari - 211331200503233

Seetha Lakshmi C - 21133120050

Shalini M - 2113312005034

Sumithra S - 2113312005039

Comments

Post a Comment